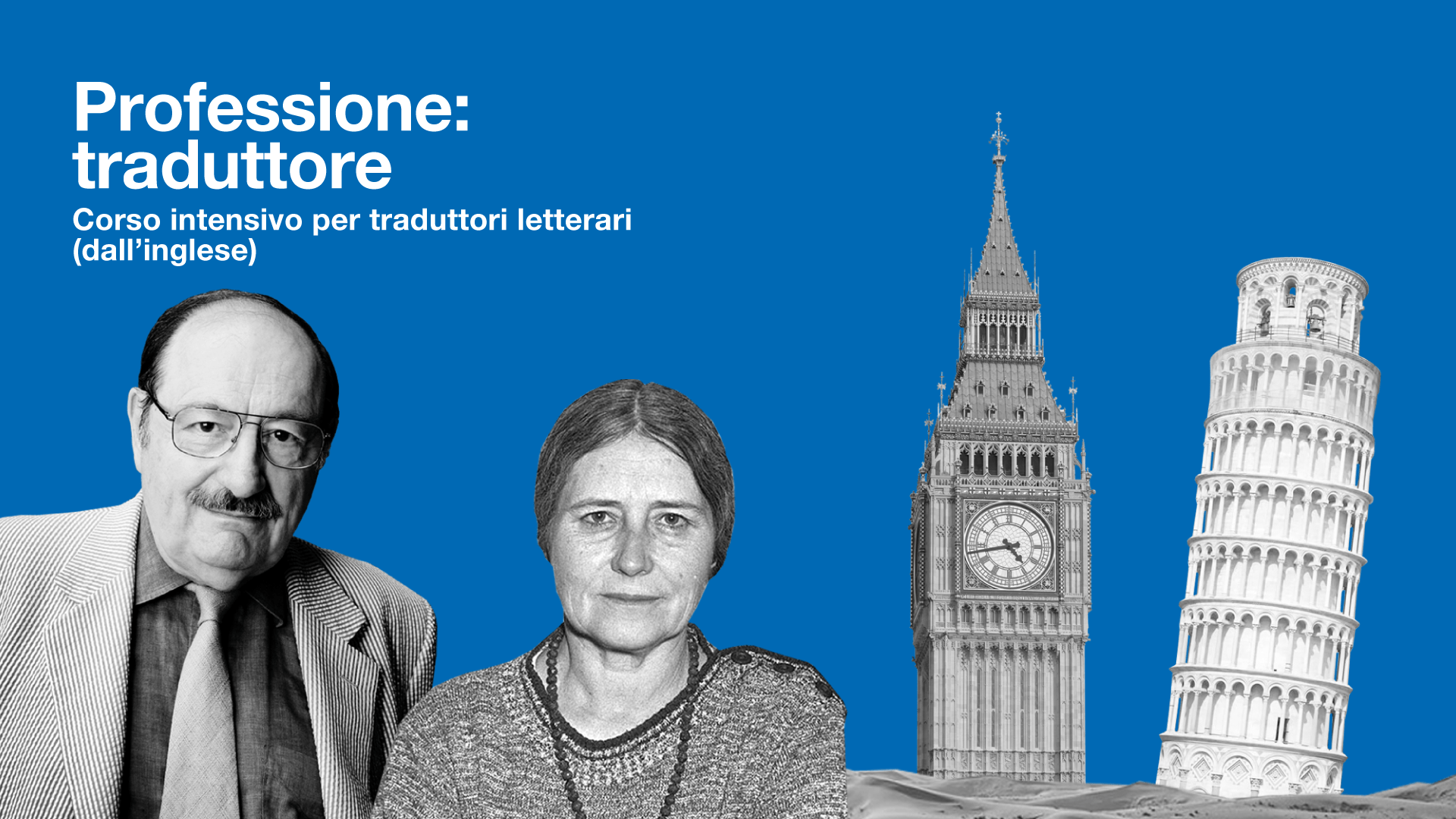

Giulia Costa è la vincitrice della borsa di studio di Professione: traduttore, il corso intensivo per traduttori letterari dall’inglese con Damiano Abeni, Federica Aceto, Isabella C. Blum, Gaja Cenciarelli, Luciana Cisbani, Gioia Guerzoni, Franco Nasi, Francesca Novajra, Silvia Pareschi, Tim Parks, Sara Reggiani, Giovanna Scocchera, Francesca Serafini che si terrà online dal 1 ottobre.

Il bando della borsa di studio chiedeva ai partecipanti di tradurre un estratto da Oh God, The Sun Goes di David Connor. Ecco la versione in lingua originale:

I T’ S A S S I M P L E as it goes, the sun is missing. It’s missing. It’s missing. Been gone a month last someone’s seen it.

There’s a spot in the sky where it should be, a hollowed out circle that’s sort of grey, like the absence of light—not darkness, different sort of absence—in a way, it’s brighter than if the sun were there, more blinding even. Blinding grey absence in the sky.

Hard to see anything now, is what I’m saying, but still people are making do best they can. People are still moving along with their lives, going to work, going to school, cutting their nails, doing the laundry. It’s only been a month.

Take Tom and Pete for instance. The two of them are sitting at a diner eating eggs. That’s what they do each morning, same routine. I know this because I’ve been going to the diner each morning too, ever since the sun went missing, I’ve been eating eggs.

Usually I sit alone at a booth and watch Tom and Pete at the counter, talking about cars and roads and going. They say things about gasoline, about a woman they both know—I watch them as their yolks run down their plates.

Tempe, Arizona. Tempe. Tempe. That’s where I moved when the sun went missing, about a month ago—moved because I thought maybe I’d find the sun in Tempe, or I’d find someone who could point me in the right direction. For some reason I thought Tempe when the sun went missing.

If the sun were underwater, I’d get a worm and fish it out.

If the sun went in a cave, I’d grab a flashlight and go searching. If the sun went to bed, somehow tucked itself under the covers and went to sleep, I’d find my way into its dream and say wake up, wake up. But none of these seem to be the case— for some reason, I thought Tempe, so I moved to Arizona.

I’m staring down at two eggs now, two eggs on my plate staring back up. There’s a way that eggs stare that’s more like looking, looking not staring, like the difference between see- ing and eying. My eggs can’t see me, is what I’m saying, of course they can’t—they’re eggs, I’m joking, okay okay, the waitress comes over and refills my glass.

Today, I’ve got a meeting with a Dr. H.A. Higley. I read an article about Dr. Higley in the newspaper that said he knew where the sun was, or at least that he’d been studying its movement for the past forty years. I found his number in a phone book and gave him a call because I figured he might know where to point me.

In the corner of the diner, Tom and Pete are still digging into their eggs. One of them makes a joke and the other slaps his knee like a cartoon stooge. In the other corner, there’s a jukebox and Tom goes over to play a song on it. He shouts something to Pete and slips in a coin.

Wonder this time where she’s gone . . .

“Jesus Christ,” shouts Pete, putting down his fork. The eggs on his plate start running, and Tom comes over with a big smile like a kid who’s made a stupid joke.

Wonder if she’s gone to stay . . .

“Come on,” says Tom, reaching for Pete’s hands. Pete pulls away and Tom laughs a little. “Pete, give me your hands,” he says.

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone . . .

And this house just ain’t no home . . .

Anytime she goes away . . .

“Withers?” says Pete.

“Why not?” says Tom. “It’s a good song.”

Traduzione di Giulia Costa

È MOLTO SEMPLICE, il sole è scomparso. È scomparso. È scomparso. È da un mese che non si vede più.

Al suo posto, nel cielo c’è una chiazza, un cerchio vuoto di una specie di grigio, come un’assenza di luce. Non è oscurità, ma un altro tipo di assenza; in un certo senso, è più luminoso di quando c’era il sole, addirittura più accecante. Un’assenza grigia e accecante nel cielo.

Quello che sto cercando di dire è che si fa fatica a vederci ora, ma la gente tira avanti come può. Le persone continuano con le loro vite, vanno al lavoro, vanno a scuola, si tagliano le unghie, fanno il bucato. È passato solo un mese.

Prendete Tom e Pete, ad esempio. Quei due sono in un diner a mangiare uova. È quello che fanno ogni mattina, la stessa routine. Lo so perchè anch’io vado al diner ogni mattina, da quando il sole è sparito, e mangio le uova.

Di solito mi siedo da solo a un tavolo con i divanetti e guardo Tom e Pete al bancone, che discutono di macchine e di strade e di andarsene. Parlano di cose tipo la benzina, e di una donna che entrambi conoscono… Li osservo mentre i tuorli si spargono sui loro piatti.

Tempe, in Arizona. Tempe. Tempe. È lì che mi sono trasferito quando il sole è scomparso, circa un mese fa. Ci sono andato perchè pensavo che magari a Tempe avrei trovato il sole, o qualcuno che potesse indicarmi la giusta direzione. Per qualche motivo, quando il sole è scomparso, ho pensato: Tempe.

Se il sole fosse sott’acqua, mi procurerei un’esca e lo pescherei.

Se il sole fosse nascosto in una caverna, prenderei una torcia e andrei a cercarlo. Se il sole fosse andato a letto, se in qualche modo si fosse infilato sotto le coperte e si fosse addormentato, cercherei di intrufolarmi nel suo sogno e gli direi svegliati, svegliati. Ma sembra non essere così. Tempe, ho pensato, per chissà quale ragione, allora sono andato in Arizona.

Ora sto fissando due uova, due uova che a loro volta mi fissano dal piatto. Hanno un modo di fissare, le uova, che è più simile al guardare; guardare, non fissare, la stessa differenza che c’è tra vedere e osservare. Le mie uova non possono vedermi, voglio dire, naturalmente non possono, sono uova; sto scherzando, okay okay, la cameriera si avvicina e mi riempie il bicchiere.

Oggi ho un appuntamento con un certo Dottor H.A. Higley. Ho letto sul giornale un articolo a proposito del Dottor Higley, dove si diceva che sapesse dov’era il sole, o almeno che ne avesse studiato il movimento per gli ultimi quarant’anni. Ho trovato il suo numero in un elenco telefonico e l’ho chiamato, ho pensato che forse saprà indicarmi una direzione.

In un angolo del diner, Tom e Pete stanno ancora mangiando le loro uova. Uno di loro fa una battuta, e l’altro si batte la mano sul ginocchio, come in una vignetta. Nell’angolo opposto c’è un jukebox, Tom va a scegliere una canzone. Grida qualcosa a Pete e inserisce una moneta.

Wonder this time where she’s gone . . .

“Oh Gesù!” esclama Pete, abbassando la forchetta. Le uova sul suo piatto iniziano a colare, Tom si avvicina con un gran sorriso, come un bambino che ha fatto una battuta stupida.

Wonder if she’s gone to stay . . .

“Dai,” dice Tom, e fa per prendere la mano di Pete. Pete si scansa e Tom fa una risatina. “Dammi la mano Pete”, insiste.

Ain’t no sunshine when she’s gone . . .

And this house just ain’t no home . . .

Anytime she goes away . . .

“Withers?” chiede Pete.

“Perché no?” dice Tom. “È una bella canzone.”

Commento di Sara Reggiani

Vorrei premiare Giulia Costa perché tra tutte mi sembra quella che ha adottato le scelte più consapevoli: ha mantenuto il ritmo delle frasi, il tono colloquiale e il registro giusto. Ha restituito quell’atmosfera sospesa che è la cifra principale del libro. Non ci sono calchi, c’è l’uso della punteggiatura all’italiana. Le imperfezioni ci sono ma Giulia dimostra di sapere già cosa guardare.